Release date

Field Research Around Qaanaaq Coast, Northwestern Greenland 2025

Table of contents

Research teams of the Research Program on Coastal Community in the fields of marine, glaciers/ice sheet, land/atmosphere, humanities, or others conduct a variety of research observations around Qaanaaq in northwest Greenland from July to September 2025. Please enjoy reports from the research teams along with photos.

Marine mammal survey around Qaanaaq

Post Date:

Author: Yuta Sakuragi, Sara Kim, Yoko Mitani (Kyoto University)

The people of Qaanaaq rely on hunting marine mammals such as seals and narwhals for their livelihoods. To better understand the interactions between humans and marine mammals, we conducted research on the marine environment, the ecology of marine mammals, and the everyday lives of local residents (Photo 1).

For the oceanographic survey, we deployed instruments at several sites within the fjord to measure water temperature and salinity. We also collected phytoplankton and zooplankton samples using water samplers and plankton nets (Photo 2). We conducted visual surveys of marine mammals during boat trips between observing sites. Observers scanned the sea from boats with binoculars, and by recording the sighting locations of different species, we can identify species-specific distribution patterns. Continuous monitoring will also help us track how these distribution change of marine mammals in response to climate change. This year, we observed several species, including ringed seals, bearded seals, harp seals, and narwhals (Photos 3 and 4).

We also joined local hunters during seal and narwhal hunts to conduct visual surveys, behavioral observations, and acoustic monitoring. From the harvested animals, we collected samples such as muscle, liver, and stomach contents. These samples will be analyzed to determine their diet and contaminant levels. Joining the hunts gave us an invaluable opportunity to observe Indigenous hunting practices and daily lives firsthand (Photo 5).

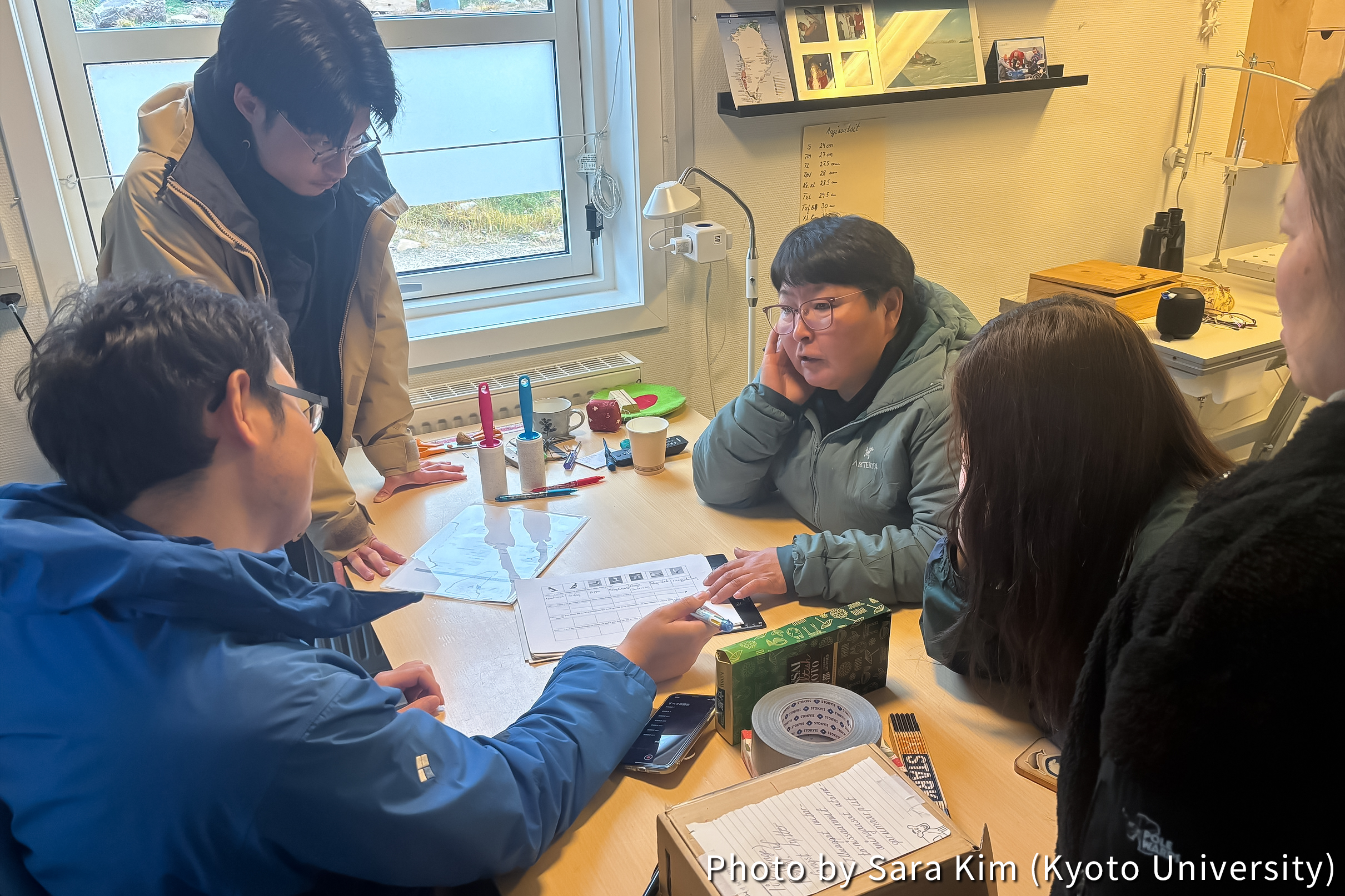

In addition, we conducted interviews with Qaanaaq residents to learn more about how closely their lives are connected with the marine ecosystem (Photo 6). The interviews focused mainly on diet, but also covered other aspects of daily life.

Through this fieldwork, we obtained not only distribution data and biological samples of marine mammals, but also valuable insights on the lives of local people. By analyzing the data and samples we collected, we aim to shed light on the complex interactions between marine mammals and the communities living in the Arctic.

Sampling of arctic char by gillnets

Post Date:

Author: Shoma Tsujimura, Tomiyasu Makoto (Hokkaido University)

This summer, I’m conducting Arctic char sampling in the marine areas near Qaanaaq, northwestern Greenland. This fish belongs to the salmon family and lives in the Arctic region. Every summer, when the sea ice breaks up, they descend from inland freshwater lakes to the sea and migrate near the shore to search for food. In the waters around Qaanaaq, Greenland, where the ArCS III coastal community project is focused, local residents use fence-like gillnets to catch these fish, which are an important summer food source for them. This time, we are using gillnets employed by local residents to catch fish, collecting biological information, sampling stomach contents, and gathering data on fishing methods (Photos 1 to 4). There is little biological data available for Arctic char in this sea area, and I find it a very interesting topic, including its relationship with local community utilization. Going forward, we plan to analyze the data collected this time to clarify the characteristics of individuals and their spatio-temporal feeding ecology.

Arctic char fishing in Qaanaaq is unique, with fishing taking place in shallow waters only 20 to 30 meters from the shore, and a system established where one person operates a gillnet. The fishing grounds have a large tidal range, with the seabed exposed at low tide and a water depth of about 1.5 to 2.0 meters at high tide. Therefore, the nets are set according to the tidal changes. As the tide comes in, the nets are spread out and tensioned, which is how the Arctic char is caught (Photos 5 to 7).

I feel that this fishing method effectively leverages local traditional knowledge by making use of both the Arctic char’s ecology and the unique characteristics of the location. This time, we aim to investigate not only the collection of biological information but also aspects related to fishing efficiency, such as the spread of gillnets and their relationship with the timing of catches.

Workshop in Qaanaaq, Northwest Greenland –

Post Date:

Author: Sara Kim(Kyoto University), Takuro Imazu (Hokkaido University)

Photo 1: Many people gathered at the workshop

Photo 1: Many people gathered at the workshop

On August 4, our team organized a community workshop in Qaanaaq, a village in northwestern Greenland, as part of our ongoing engagement with local people. Nearly 50 people from the community gathered at the village gymnasium to take part in the event (Photo 1).

The workshop began with welcome remarks from our key local supporter, Ms. Toku Oshima, followed by an introduction to the theme of coastal community challenges from Professor Sugiyama (ARC, HU). Five researchers then presented their recent findings. First, Specially Appointed Assistant Professor Ogawa (NIPR) reported on marine mammal surveys and future research requests from the community (Photo 2).

Next, Associate Professor Podolskiy (ARC, HU) presented the results of acoustic observations and research on narwhal ecology. PhD candidate, Mr. Imazu (GSES, HU) reported on recent ice mass loss of Qaanaaq Glacier and its meltwater discharge, while Specially Appointed Assistant Professor Sakuragi (WRC, KU) shared results from satellite tags deployed on ringed seals to investigate their habitat use. Finally, Assistant Professor Tomiyasu (FFS, HU) presented scientific insights into the ecology of Greenland halibut and traditional fishing practices of the local community. The lively discussions with local participants demonstrated their strong interest in our research and its outcomes (Photo 3).

-

Photo 2: Presentation by Dr. Ogawa

Photo 2: Presentation by Dr. Ogawa -

Photo 3: Communication with local people

Photo 3: Communication with local people

During the break, we served sushi rolls, okonomiyaki, and Japanese snacks, which were very well received, with many commenting “mamartoq” (“delicious”) (Photo 4).

In the latter half of the workshop, we also shared feedback by screening the NHK BS program “Frontiers: Scientists × Indigenous Peoples — The Reality of the Arctic”, broadcast on August 2, which featured coverage of last year’s ArCS II project on coastal environmental issues.

We will continue to devote ourselves to returning research findings to the community and addressing local challenges through our ongoing research activities (Photo 5).

-

Photo 4: Sushi, okonomiyaki and Japanese snacks served during the break time

Photo 4: Sushi, okonomiyaki and Japanese snacks served during the break time -

Photo 5: Commemorative photo with all participants

Photo 5: Commemorative photo with all participants

Field campaign in Bowdoin Glacier, northwestern Greenland

Post Date:

Author: Kotaro Yazawa, Fumi Mikome, Takuro Imazu, Shin Sugiyama (Hokkaido University)

Calving glaciers are losing the mass by melting and calving. To investigate processes of the ice loss in calving glaciers, we conducted field observations on August 2, 6 and 18 at Bowdoin Glacier, a calving glacier in northwestern Greenland (Photo 1).

Bowdoin Glacier has been surveyed on July in 2013–2017 and 2019, making this campaign the first observation in six years. The glacier is about 3 km wide, and moved 400–600 m per year, and the front of the middle part retreated by ~650 m between 2019 and 2025. From our base in Qaanaaq village to Bowdoin Glacier, it took about one and a half hours by a boat (Photo 2). At the glacier terminus, we watched seabirds passing under “an ice arch” (Photo 3).

During the survey, we installed time-lapse cameras and an acoustic sensor and performed the drone surveys (Photos 4, 5). We took photos of the glacier front at each 10 min by time-lapse cameras to measure the ice velocity and calving volumes. The sounds of calving events were recorded by the acoustic sensor to understand the calving frequency.

Drone surveys were conducted three times, covering an area of about 10 km². Surface elevation changes and calving volumes will be quantified during the study period, using ice surface 3-D models generated from photos of UAV surveys. We can also detect surface crevasses in detail from drone imagery (Photo 6). Image analysis on crevasses should contribute to understanding calving processes. We were nerves when we operated the drone in the sleet and bad weather, but we were relieved to complete the survey safely (Photo 7). During the survey, we heard the loud sounds of calving and felt the ice movement firsthand, which reminded us of the grandeur of the Arctic environment once again. We will analyze the valuable data to better understand calving glaciers.

Greenland observations started!!

Post Date:

Author: Evgeny Podolskiy (Hokkaido University)

Japanese translation: Monica Ogawa (NIPR)

After two cancellations of flights bound for Qaanaaq, our 11-person ArCS-3 Greenland team was stranded in Ilulissat (Greenland). Both cancellations occurred within just four days for the same reason: fog over Qaanaaq Airport. Poor visibility caused the aircraft — with deployed landing gear — to abort landing and return. For half of the team, this means we have already spent nearly 10 hours flying between Ilulissat and Qaanaaq! Our local host said that flying to Qaanaaq is more difficult than flying to the Moon, and it’s hard to disagree since we left Japan a week ago! Our next chance is in a few days, and we hope for the best. Fingers crossed (Photo 1, 2).

Meanwhile, Ilulissat is renowned for its stunning Ice Fjord, a UNESCO World Heritage Site where large baleen whales swim among massive icebergs. Wealthy tourists pay a lot to visit this incredible place, and we are taking advantage of this free opportunity to explore the fjord, enjoy good food, and test our equipment. For example, in the last 24 hours, we could try local seafood and conduct a whale survey from the restaurant over breakfast (just kidding;) – without some humor, Arctic research is a hopeless thing) (Photos 3,4).

Actually, we could collect images of whales 4 km away using an Uncrewed Aerial Vehicle. It was amazing to see a humpback whale, fin whale, and seagulls foraging together. At the same time, a real-time hydrophone recording system was used to try to capture whale calls and ocean noise. Compared to Qaanaaq, Ilulissat’s port is very noisy and busy, particularly with halibut (a type of flatfish) fishing boats and cruise ships. More tests and photos are coming, so stay tuned! (Photos 5and 6).